by Matt Hayes

The cassava just wouldn’t cook right.

The improved variety grew incredibly well, but put it in the pot, and the expected consistency of the food just didn’t emerge. You’d boil or steam it in the traditional ways favored by generations of families of East Africa, but the root remained too hard to enjoy, especially for infants and the elderly.

So a variety with high yields and strong disease resistance just sat on the shelf.

“There are some improved cassava varieties out there that seem to offer better results for farmers, but the consumers don’t like them because they lack some attributes preferred by the consumers,” said Paula Iragaba, Ph.D. ’19, whose doctoral work at Cornell focused on understanding the social dynamics of food choices and analyzing the genetic background underpinning preferred cassava traits of smallholder farmers.

“Breeding cassava varieties that grow better is great. But if farmers don’t use them, then it’s not effective. Cassava isn’t just meant to be grown — it’s a staple food for majority of smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa,” she said. “I wanted to find a scientific way to understand the traits end-users actually want.”

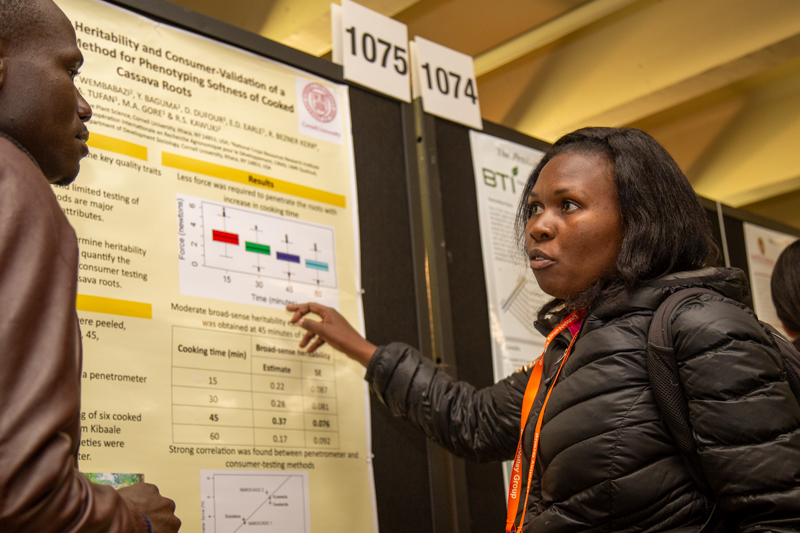

A research study funded by the NextGen Cassava project aimed at doing just that. Iragaba designed and conducted a survey of hundreds of smallholder farmers in Uganda to find out what traits they look for in cassava. Her analysis revealed that the softness of cooked cassava is a major influence on what kinds of varieties farmers actually adopt.

“If cooked cassava is hard, then the kids don’t eat it. And older people with weaker teeth can’t chew hard roots,” she said. “In some households, cassava is served at all three meals. So if the children and the older people aren’t going to eat it, then the variety won’t get adopted, no matter how well it may grow.”

Understanding what consumers want on their plate was the first step. The next was developing a reliable, low-cost method that breeders could use to assess root softness early in the breeding cycle and inform their selections.

Enter the penetrometer.

A common tool in the lab to test force, a penetrometer offered a tantalizing method to determine which varieties produced roots that would cook to a desirable softness.

Iragaba designed a study to track consumer preference with results obtained from a penetrometer. Her analysis showed a positive correlation between what farmers said they wanted and what the penetrometer showed in the lab.

“Now there’s a starting point for cassava breeders to use for measurements and to ensure that what’s being advanced in the breeding program has the desired trait,” she said.

Study co-author Mike Gore, Ph.D. ’09, professor of molecular breeding and genetics for nutritional quality, Liberty Hyde Bailey professor and international professor of plant breeding and genetics, said the findings provide powerful insights that will help reshape breeding for cassava traits preferred by smallholder farmers and end-users in Africa.

“All the advanced plant breeding technologies developed and implemented by our project and others will be useless if the improved varieties are not adopted by cassava consumers,” said Gore. “Paula’s work is an important step toward making sure Ugandans can truly benefit from these varieties, and gives us a model to follow in other countries where cassava is a key crop.”

Along with Gore, other Cornell faculty co-authors include professor Rachel Bezner Kerr and adjunct assistant professor Hale Tufan in the Department of Global Development.

Matt Hayes is associate director for communications for Global Development in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.